Why Bitcoin made it: What happened to other digital cash?

Since its public introduction in 2009, Bitcoin’s “death” has been predicted more than 420 times. But here it still stands, stronger than ever. Why did the mighty crypto rise to the top and how has it stayed there?

We’ve taken a look back at the digital cash projects that laid the groundwork for Bitcoin and examined its many intricacies to understand its continued global success.

Before Bitcoin

Bitcoin wasn’t the world’s first digital cash. In fact, there were many proposals before it.

Arguably the most famous digital cash pioneer is American cryptographer, David Chaum. In 1983, he published ‘Blind Signatures for Digital Payments’, in which he first proposed his idea for digital money using a form of cryptographically-secure digital signature. The way it works is the content of a message is disguised – or ‘blinded’ – before it’s signed. Therefore, the signer won’t learn the message’s content. The signed message is then unblinded, at which point it functions as a normal digital signature that can be publicly checked against the original message.

Blind signature technology gives users complete privacy around their transactions – sound familiar? Chaum eventually put his theory into practice in 1989 with the creation of “DigiCash”. Unfortunately, DigiCash was launched prior to e-commerce taking shape and subsequently ended up filing for bankruptcy in 1998 as online shoppers clung to the familiarity of credit cards over the anonymous alternative.

In 1997, British cryptographer Adam Back revealed his initial proposal for Hashcash. Originally created as a prevention to email spam and DDoS attacks, Hashcash used the proof-of-work algorithm that Bitcoin uses today. Back formally described Hashcash in a 2002 paper, “Hashcash – A Denial of Service Counter-Measure”. Unfortunately, as the crypto faced increasing processing power demand, which it was unable to supply, it eventually became less and less effective and eventually the platform shut down.

In 1998, Wei Dai, a computer engineer published a paper introducing his “B-money” concept. The general outline in many ways mirrors (or predates) modern-day digital currencies. Dai described B-money as “a scheme for a group of untraceable digital pseudonyms to pay each other with money and to enforce contracts amongst themselves without outside help.” B-money never officially launched and remained in existence purely as a proposal. But Dai’s work certainly didn’t go unnoticed; his contribution to the crypto world is affectionately acknowledged in Ethereum’s smallest unit of ether, called “wei”.

In 1998, Nick Szabo, a computer scientist known for his work in digital contracts and digital currency proposed “Bit Gold”. While some have speculated Szabo was behind Bitcoin, these suggestions have been debunked. Szabo’s post-2008 writings about Bitcoin reveal discrepancies between his ideology and that of Bitcoin’s Satoshi Nakamoto. Szabo viewed Bitcoin as a store of value, not as a means of exchange. Bit Gold’s most crucial issue was its inability to solve the double-spend problem inherent in digital cash – a problem common to these early incarnations of digital cash and one that Bitcoin was eventually able to solve.

Timing is everything

Bitcoin is money with a philosophy and its timing couldn’t have been more fortunate. Its release came at a time when governments’ and central banks’ ability to safely store money was facing serious questions. By 2008, US banks were paying the price for years of bad practice – risky loans, subprime mortgages, and outright fraud had consumed the system. In an attempt to prop up the system, the government used taxpayer money to bail out the banks. Incredible customer dissatisfaction followed and people’s faith in the government and banks to adequately perform their functions was shattered.

The timing was almost perfect. With trust in banks at rock bottom, conditions were ripe for an entirely new financial ecosystem that offered an alternative, one that avoided the need to rely on those who had caused such destruction. The crisis shone a light on the elephant in the room. It caused people to ask, what do banks do with our money?

Bitcoin was developed to end the reliance on trusting middlemen who’ve long been abusing our trust due to a lack of an alternative. In a broader sense, “removal of trust” sounds pretty diabolical, but think of it as a diversion of trust to something bound by logic: mathematics.

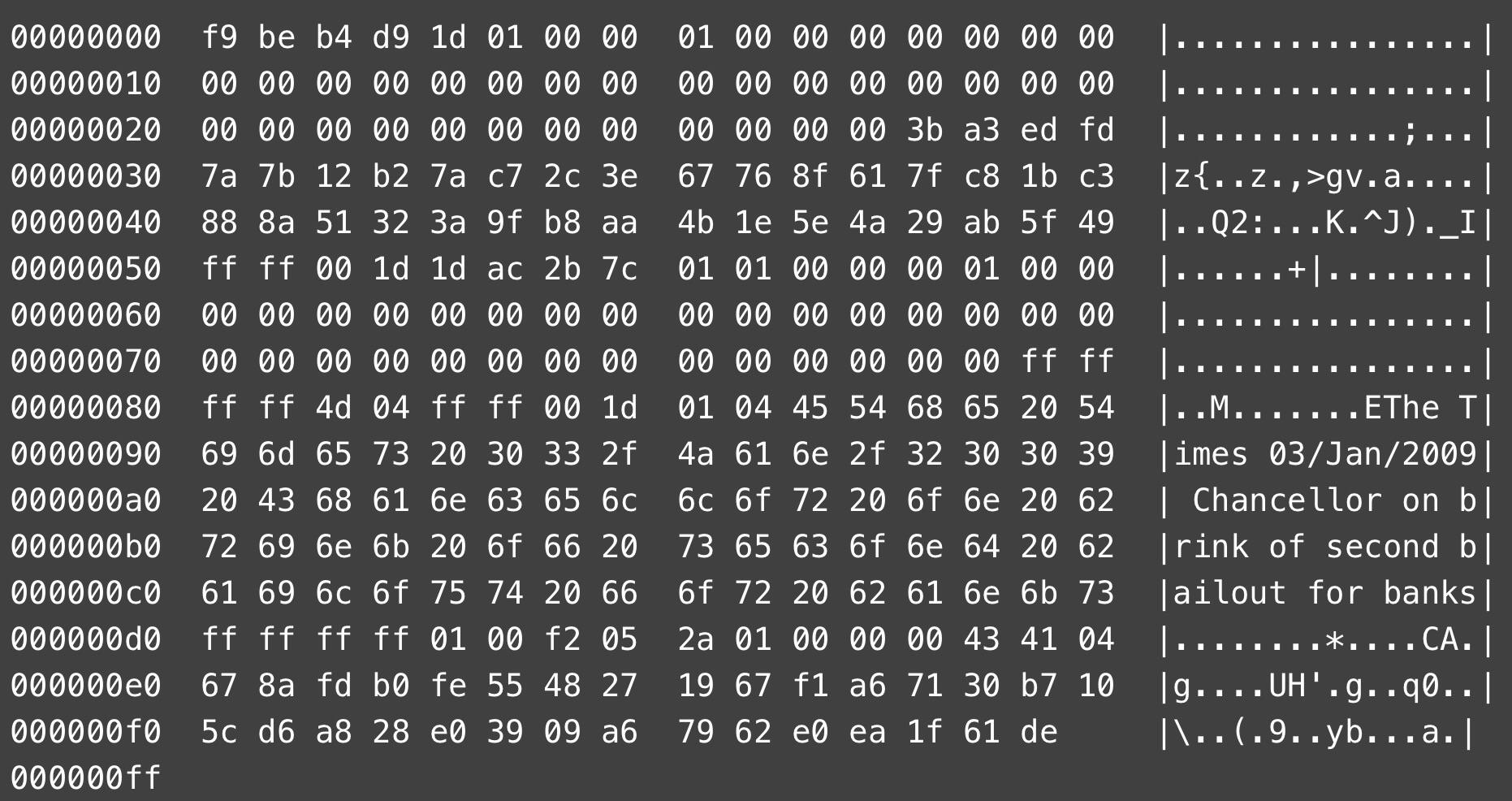

That the goal of Bitcoin is to replace such a system is evident from the message encrypted in Bitcoin’s genesis block. It read: The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks. The message was a reference to then-Chancellor of the Exchequer, Alistair Darling’s preparation of a £500Bn rescue package for UK Banks.

(Above: Bitcoin’s genesis block)

It was a clear snub toward centralised financial institutions, bank bailouts and other murky fiscal policies. Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin’s pseudonymous creator, instead put forward his idea of a peer-to-peer, decentralised currency that was not reliant on any third party.

Our current financial landscape may seem bleak at the moment. In part due to the COVID-19 outbreak, but also the decisions made by those who we conventionally trust to safeguard our money and our economic markets. As devastating as financial crises are though, they shed light onto a broken system that’s gone untouched for decades, and ultimately encourage ordinary people to create innovative solutions.

Bitcoin bust the double-spend problem

The double-spend problem was arguably the main obstacle for early attempts to introduce digital cash. The double-spend problem refers to the risk that a digital currency can be spent twice. For example, if you go to a store and buy groceries with a $20 bill, you hand it to the cashier and they’ll put it in the cash register. That money can’t be respent unless it’s been physically stolen. This isn’t true when an item is digital. Think of a photo or a movie – it’s incredibly easy to make a copy.

Bitcoin solves this problem through a confirmation mechanism and a common, universal ledger system known as the Bitcoin blockchain. A blockchain is made up of “blocks”. These are essentially files containing permanently recorded data – in this case, all recent Bitcoin transactions. Think of it like a stock transaction ledger, the difference being that the Bitcoin blockchain bundles up all the transactions and then broadcasts them to all of the nodes in the bitcoin network. As transactions are time-stamped on the blockchain and mathematically related to the previous ones. This means they are irreversible and impossible to tamper with.

So how does this put a stop to double spending? Imagine a scenario where you have 1 BTC and you try to spend it twice in two separate transactions, sending the same BTC to two separate bitcoin wallet addresses. Both transactions go into the pool of unconfirmed transactions. Transaction A would be approved via the confirmation mechanism and then verified into the subsequent block. Transaction B, on the other hand, would be picked up as being invalid by the confirmation process and wouldn’t be verified. If both transactions are sent for confirmation at the same time, the one with more confirmations is added to the blockchain.

Decentralised and open-source

The technology behind Bitcoin has a completely distributed architecture, without any single trusted entity.

While many other cryptocurrencies are decentralised, there are many that aren’t. Bitcoin Cash and Ripple’s XRP are two popular centralised cryptocurrencies. This means their platforms and the networks in which they operate are controlled by a single entity with the power to impose control over users’ coins where and if they see fit. Other digital cash projects have had to rely on a centralised bank trusted to issue the digital money and to detect potential double-spend issues.

Centralisation has its merits–such as potentially reducing levels of confusion, chaos and waste. Lesang Dikgole explains in Hackernoon, “In the present, there is a reigning predilection for decentralisation. This is, partly, for good reasons. Centralised systems carry the heavy risk of stagnancy, being-disrupted, lacking-adaptability, and over-relying on history as opposed to the present and the future.”

Centralised systems typically have a single point of failure, meaning any part of a centralised organisation can be more-easily compromised. Additionally, these systems can suffer from an over-exertion of reach to suit the agenda of whoever controls it–this could be politically motivated, or otherwise. As centralised organisations tend to store data in one facility, they’re also more primed to sustain hacks, as opposed to their decentralised counterparts.

Kyle Torpey raises an interesting example around governments’ hand in controlling public access. He explains that: “Imagine if Bitcoin was originally structured like Ripple or Stellar. What would have happened when US Senators Chuck Schumer and Joe Manchin demanded a crackdown on Silk Road and Bitcoin back in 2011? Would the peer-to-peer digital cash system still exist?” Sure, Silk Road posed a threat to society in so far as what was available for purchase, where something like Bitcoin is vastly on the opposite spectrum. But Bitcoin has outgrown this image as a tool for criminals, and if it had been so vulnerable to knee-jerk reactions from politicians, we may never have discovered this.

Just as governments are able to manipulate the supply and value of any currency, by imposing any number of monetary and fiscal controls, centralised cryptocurrencies face the same potentially-devastating scenarios. The value of any currency, crypto or otherwise, should not have the ability to be tampered with on a whim. Generally, the more centralised something is, the more cooks there are in the kitchen–and every cook wants their piece of the pie.

Castle Island Ventures Partner Nic Carter wrote about how thousands of Bitcoin competitors that have popped up over the years have missed the point of this new technology. On an episode of Laura Shin’s Unchained podcast, Carter spoke about the perils of centralisation, using the EOS altcoin as an example, saying: “[A high degree of centralization] poses a greater threat to the long-term legitimacy of the network, which is not outweighed by the marginal technical enhancement there.”

Conversely, Bitcoin’s ecosystem is designed in such a way that ensures its users have economic incentives to participate. Think mining rewards and the option to collect transaction fees. Bitcoin’s open-source software means it’s constantly maintained by an active community, constantly striving to improve on the crypto’s offerings. Bitcoin doesn’t demand users trust one person or company–by having skin in the game bad actors are fundamentally deterred from abusing the system.

Bitcoin’s network effect

The biggest hurdle to any project’s success is adoption, which, in turn, adds legitimacy. Bitcoin is the most accessible cryptocurrency; it’s available on more exchanges, through more merchants and has more software and hardware that supports it than any other cryptocurrency.

Bitcoin also has the largest developer ecosystem, and according to Bitcoin activist and developer Jimmy Song, with “more software and more implementations than any altcoin.” Any competing altcoin would face a herculean task to break those barriers.

As previously mentioned, Bitcoin’s incentivisation model propels and expands its network. The more people who consider it a store of value incentivises more miners to secure the network.

More recently, Bitcoin has received institutional investors’ so-called stamp of approval as the crypto found its way into the product offerings of firms like Grayscale and ARK Investment Management. Following these trends, banking behemoths like Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan are increasingly acknowledging Bitcoin’s status.

Altcoins and future utility

“Most altcoins have some technical difference compared to Bitcoin and that is often the reason given for why people invest in them. The reasoning is that since these altcoins have much of the same utility of Bitcoin plus something else, the altcoin can be more useful than Bitcoin and thus take over,” says Jimmy Song, a Bitcoin advocate, developer and author. He claims, however, that a feature shown to be useful is likely to be adopted into Bitcoin itself, but most haven’t yet proved themselves useful.

Altcoin creators, therefore, don’t only contend with Bitcoin or other top market cap cryptos, but with entrepreneurs looking to build something on Bitcoin. Song believes it’s more likely that “Bitcoin in one form or another will consume other use cases nullifying any advantage an altcoin might have.”

Many have compared cryptocurrency to the dotcom era of the 1990s and early 2000s, with predictions around the demise of altcoins following the same path. Futures and forex career trader and author, Peter Brandt tweeted in 2019 that altcoins without legitimate value will eventually die out once the hype has settled.

Equally, however, with any new technology being first to market is often not the panacea it’s made out to be. Mark Zuckerburg didn’t invent the social network, Steve Jobs didn’t invent the computer and Larry Page didn’t invent the search engine – they all built and improved on what was already there. So who’s to say that something won’t come along that can improve on Bitcoin? Without a clear use case and a strong value proposition, though, it’s going to have to be something special to claim that top spot.

Discover

Discover Help Centre

Help Centre Status

Status Company

Company Careers

Careers Press

Press