Why we need a ‘trustless’ banking alternative

Have we always been a trustless society? How did the concept of trust work in tribes, and how did it evolve in the context of cities, where millions of people interact? In a global, interconnected society of billions, what does trust mean today?

These are all questions Po Chi Wu, Ph.D., a self-proclaimed Innovation Provocateur, posed in a piece on Trust in a Trustless Society. As mundane processes become automated and we become increasingly familiar with performing functions digitally, rather than in-person, what happens to our sense of trust? Is it easier to trust a system, or a person, when we’re confronted with a physical face-to-face exchange? How do we implement and retain integrity when the way we do things has changed so rapidly? Wu continues, “If we are forced to admit we can’t trust anyone, how can we organise our social structures, including government, financial institutions, healthcare, so we can protect ourselves? Clearly, we have to accept this responsibility for ourselves. No one else can or will take care of us.”

Discussions around trust are rooted in a variety of camps: sociological, psychological, political, and the list goes on. When there’s a breach of trust, as individuals, it’s assumed we take some type of appropriate action. A “fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me” kind of narrative. We end relationships, we cancel subscriptions, we change providers. In other words, we look for an alternative. But what if there isn’t a seamless alternative?

Trust has always been the bedrock of the financial system. This has been the result of necessity rather than design – even when the people in positions of trust prove themselves untrustworthy. With technology, however, this is becoming increasingly unnecessary. Trust is arguably the driving force behind cryptocurrencies, and more importantly, the lack thereof in our traditional financial systems. We’ve looked back at why people have grown to distrust many areas of the financial services sector, and why they’re looking to Bitcoin to take back control of their finances.

In what do we trust?

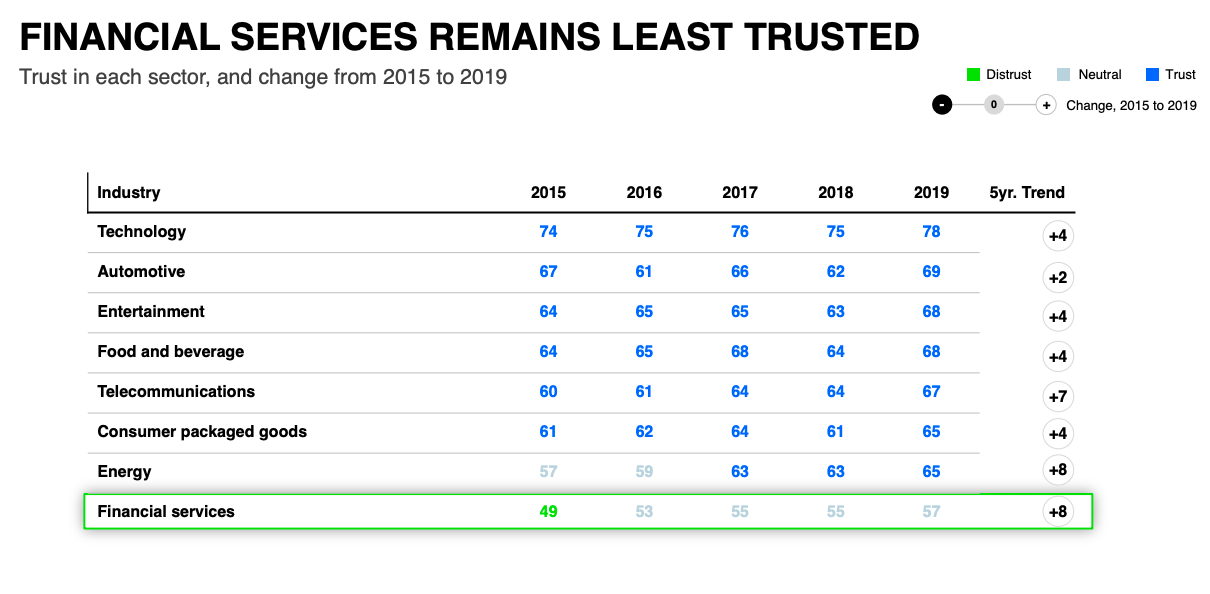

“Trust is the bedrock of financial institutions. Yet trust in the financial sector lags even trust in government, itself now at a 50-year low, according to recent survey data from Pew, Edelman, and Harris. This is not merely an economic issue, or even a legal issue. It is also a social and moral issue.” (Rebuilding Trust in the Financial Sector)

(2019 Edelman Trust Barometer)

The absence of trust is easy to explain. If we look back through history, some of the biggest financial scandals have taken place in the financial sector, by the mighty entities we entrust our most precious, hard-earned resource with: our money. This is not to say all banks, or even the majority, do not have the best of intentions. But here are just a few instances that have led some to consider an alternative solution.

Wells Fargo: The collapse of a giant

Wells Fargo, the fourth-largest bank in the United States agreed to pay a whopping $3 billion to settle its long-running civil and criminal probes into the accusations of rampant fraudulent sales practices. In an attempt to reach ludicrous sales and revenue goals, Wells Fargo executives pressured rank-and-file bank personnel to aggressively cross-sell products, leading to the creation of millions of savings and checking accounts for customers without their knowledge or consent.

Using a variety of fraudulent tactics, like “pinning”, a process in which a customers’ bank PIN number is set to “0000”, allowing bankers to readily control clients’ accounts. Or using bank employees’ own personal contact information on forms to prevent customers from discovering the scams, countless Wells Fargo employees were accused of moving money out of existing accounts and into new ones.

Even if accounts were unfunded, the creation of new accounts indicated an increase in Wells Fargo sales, leading to an increase in shares. As shares rose, the CEO and other top executives got exorbitant bonuses, and shareholders were happy. Employees who noticed discrepancies or acted as whistleblowers were either threatened with corrective action or fired on the spot and left unlikely to work in banking again.

Emily Glazer, a reporter at the Wall Street Journal, covered the Wells Fargo account fraud. She noted from the very beginning the manner in which the bank misused its high trust rankings for their own nefarious gain. She explained, “Wells Fargo was the only big bank that in their earnings report, would have the ratio of how much they cross-sold to different customers in different divisions.” She emphasises that the use of the term “cross-selling” is not conventional in the banking sector and represents the number of products they could tie a consumer into. These ranged from mortgages, car insurance, to credit cards, and so on.

She continues, “Numbers that are disclosed in earnings reports certainly do matter for the stock price and how investors are going to spend their money. Banks have shareholders to answer to, and shareholders want to hear about growth and executives want to talk about growth because they want to make more money. At this point, Wells Fargo is the most valuable bank in the world. Where are they going to get that growth from?”

It’s clear that this means of attaining high sales figures is not sustainable; at some stage, everyone is going to have a bank account. The greed for profit left bank executives blind to the function they initially set out to perform. This is a disturbing trend in the banking industry and rather uncomfortably, Wells Fargo is not alone in this. Most major banks around the world have found themselves entangled in some type of similar fraud or scandal fuelled by desperation to stay “top dog”.

HSBC’s ties with Mexican drug cartels

Who would have thought HSBC allegedly provided money-laundering services to various drug cartels, including bulk movements of cash from the bank’s Mexican unit to the US with little or no oversight of the transactions? HSBC reportedly also conducted transactions with Iran, removing references to the country in an effort to conceal them. It’s worth noting these banks, among others, have been cited numerous times and have settled numerous charges but something doesn’t seem to stick. Things don’t change.

“Lacking in these instances is a corporate culture that prizes integrity [over profit]. Enabling the business of drug running and state-sponsored terrorism in the pursuit of profit leads to dire societal consequences. Blame may be placed at the foot of the banks and regulators alike.” (Marc L. Ross, HSBC’s Money Laundering Scandal)

UK banks and “persistent misconduct”

In the United Kingdom, it was reported in 2016 that “persistent misconduct and an aggressive sales culture has cost the UK’s banks and building societies £53bn in fines, compensation and legal fees over the past 15 years.” (Jill Treanor, The Guardian) The most pervasive of all the recent UK bank scandals is the payment protection insurance (PPI) misselling, which reached £37.3bn – about four times the cost of the 2012 London Olympics. John McFall, the former Labour MP who used to chair the Treasury select committee, said: “The profitability of UK retail banks has been imperilled by persistent misconduct and an aggressive sales-based culture. This has made every citizen poorer through our pension funds and our ownership of the bailed-out banks.”

Sound familiar? Inadequate KYC (know-your-customer) and AML (anti-money laundering) controls have been at fault for many of these too-big-to-fail institutions’ mishaps, but more importantly, a disturbing disdain for morality and ethical business practices trumps them all. And, at the end of the day, the poorest consumer is always the hardest hit.

Trust the math, not the man

While a serious restructuring of consumer protection policies and the prevention of banking misconduct is desperately needed, perhaps it’s finally time for society to relook at how we interact with our financial institutions and the power we give unto them.

Cryptocurrencies, and Bitcoin, in particular, was developed to end the reliance on trusting middlemen who’ve long been abusing our trust due to a lack of an alternative. In a broader sense, “removal of trust” sounds pretty diabolical, but think of it as a diversion of trust to something bound by logic: mathematics.

Bitcoin’s release came at a time when governments’ and central banks’ ability to safely store money was facing serious questions. By 2008, US banks were paying the price for years of bad practice – risky loans, subprime mortgages, and outright fraud had consumed the system. In an attempt to prop up the system, the government used taxpayer money to bail out the banks. Incredible customer dissatisfaction followed and people’s faith in the government and banks to adequately perform their functions was shattered.

The timing was almost perfect. With trust in banks at rock bottom, conditions were ripe for an entirely new financial ecosystem that offered an alternative, one that avoided the need to rely on those who had caused such destruction.

The crisis shone a light on the elephant in the room. It caused people to ask, what do banks do with our money? If you think the $1,000 you deposited in your bank account is all there, unfortunately, we’ve got news for you. Banks employ a practice called fractional reserve banking. This means they are only required to keep a small percentage of the actual amount you deposit in your account, allowing them to invest or loan the rest, which is okay until everyone decides to draw all the money out of their accounts. While highly unlikely, if it were to happen, banks would collapse due to the inability to liquidate all funds.

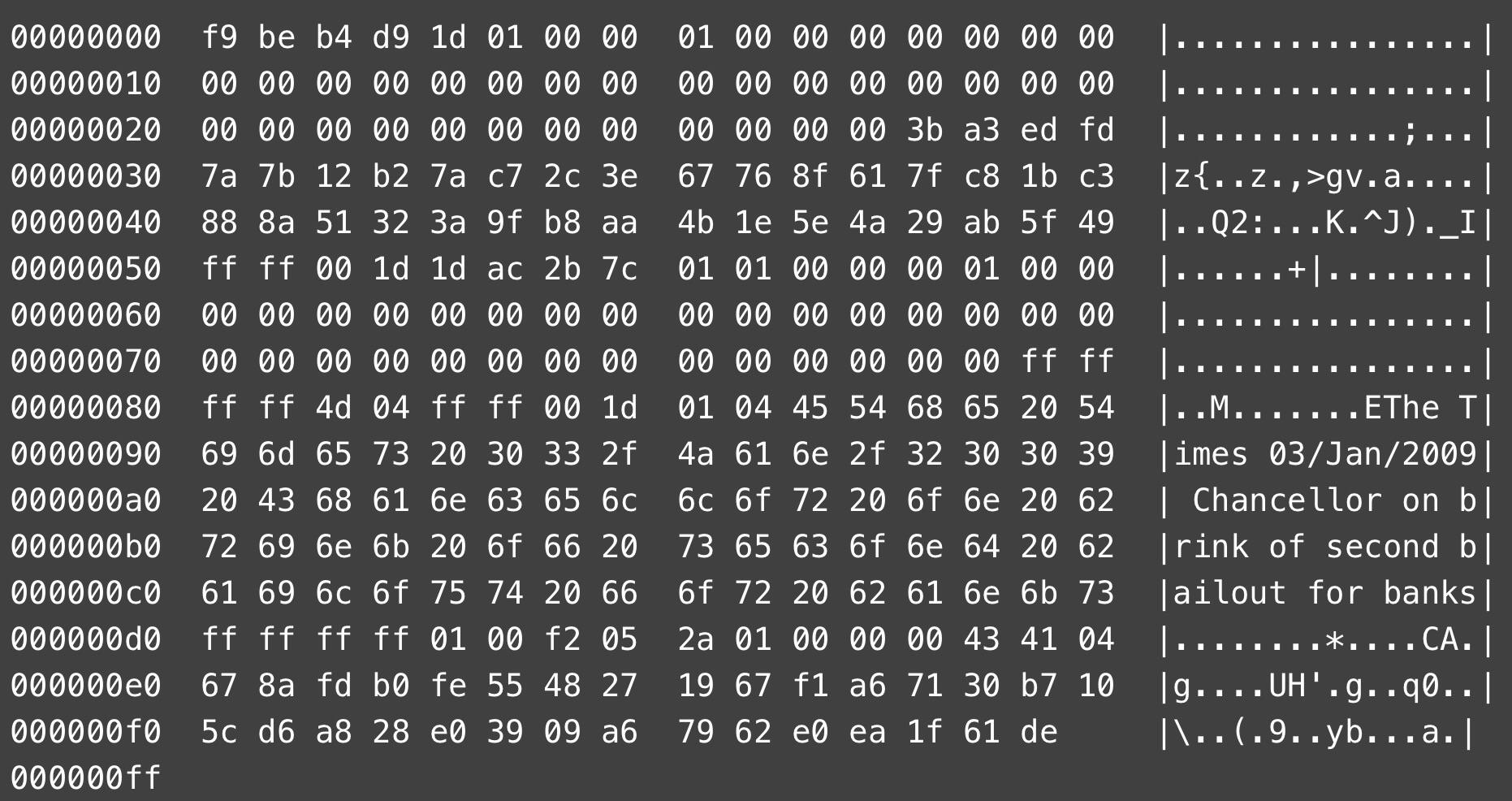

One of the biggest reasons people attribute Bitcoin’s inception to the financial crisis is the message that was encrypted in Bitcoin’s genesis block. It read: The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks. The message was a reference to then-Chancellor of the Exchequer, Alistair Darling’s preparation of a £500Bn rescue package for UK Banks.

(Source: https://www.coindaily.co/tomorrow-it-will-be-10-years-since-satoshi-created-the-genesis-block/)

It was a clear snub toward centralised financial institutions, bank bailouts and other murky fiscal policies. Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin’s pseudonymous creator, instead put forward his idea of a peer-to-peer, decentralised currency that was not reliant on any third party.

Our current financial landscape may seem bleak at the moment. In part due to the COVID-19 outbreak, but also the decisions made by those who we conventionally trust to safeguard our money and our economic markets. As devastating as financial crises are though, they shed light onto a broken system that’s gone untouched for decades, and ultimately encourage ordinary people to create innovative solutions.

Discover

Discover Help Centre

Help Centre Status

Status Company

Company Careers

Careers Press

Press