Project Dunbar and the future of a CBDC in South Africa

Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) is a touchy subject in the crypto community for the same reason that Bitcoin is a touchy one for most governments. But CBDCs aren’t going anywhere and will become increasingly relevant as governments lock in efforts and spending towards developing their versions of digital currencies hosted on distributed ledger technology (DLT).

South Africa (SA) too has been no slouch in keeping up with the global race for an integrated, cross-border CBDC. Following on from earlier work on Project Khokha, a CBDC project in partnership with Consensys and certain SA-based banks, the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) recently announced its role in the successful completion of Project Dunbar, a prototype multi-CBDC platform for international settlements. Dunbar was developed in partnership with the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) Innovation Hub and the central banks of Australia, Malaysia and Singapore.

With Dunbar, researchers aimed to solve the big question of how CBDCs by different governments could integrate on one platform. “A common platform is the most efficient model for payments connectivity but is also the most challenging to achieve,” says Andrew McCormack, Head of the BIS Innovation Hub Centre, in a joint press release. Researchers set out to tackle the biggest hurdles, relating to access, jurisdictional boundaries and governance. The project delivered two successful prototypes.

“Project Dunbar proved that financial institutions could use CBDCs issued by participating central banks to transact directly with each other on a shared platform,” a joint media release by the various participants says. “This has the potential to reduce reliance on intermediaries and, correspondingly, the costs and time taken to process cross-border transactions.”

If you don’t have the mental energy to read through the entire Project Dunbar report, and understandably so, we have pre-empted a few questions and answered them below.

A quick recap, what is a CBDC?

A CBDC is the modern, digital version of central bank money.

Explain again what the difference is between a commercial bank and a central bank?

A central bank is in charge of a country’s monetary policy and regulates how much of that country’s currency is in circulation at any given time. The SARB is the central bank of South Africa and has the power to create a CBDC in the same way it has the authority to print money.

A commercial bank is a private financial institution where many people have an account in which they store their hard-earned cash and use it to make daily transactions.

You said the project delivered two prototypes, how do these compare?

Both prototypes run on a platform made up of nodes that are hosted by project participants, and access to both networks are controlled by the network operator. The two differ in the technologies they use to run the network, which ultimately decides how the nodes communicate with each other and how transactions are validated. The finer details are rather confusing and complicated for non-developers, but they can be found on page 26 of the Dunbar report.

How does a multi-CBDC platform work?

The platform is something like a shared Google Drive but instead of sharing documents in the drive, countries have shared access to each other’s CBDCs. Each participating central bank issues its own CBDC on the platform. Participating commercial banks can then hold the various CBDCs on the platform and transact directly with each other in the relevant currencies.

So, there’s more than one type of CBDC?

Correct. CBDCs can generally be grouped into two categories, namely a retail CBDC, which individuals and businesses can transact with, and a wholesale CBDC for settling trades in financial markets, for example. These two types of CBDCs can either be designed for domestic or international use.

Up until now, most projects have focused on domestic wholesale payments. Project Dunbar was specifically focused on the requirements of a multi-CBDC platform.

How would a multi-CBDC platform work in the real world?

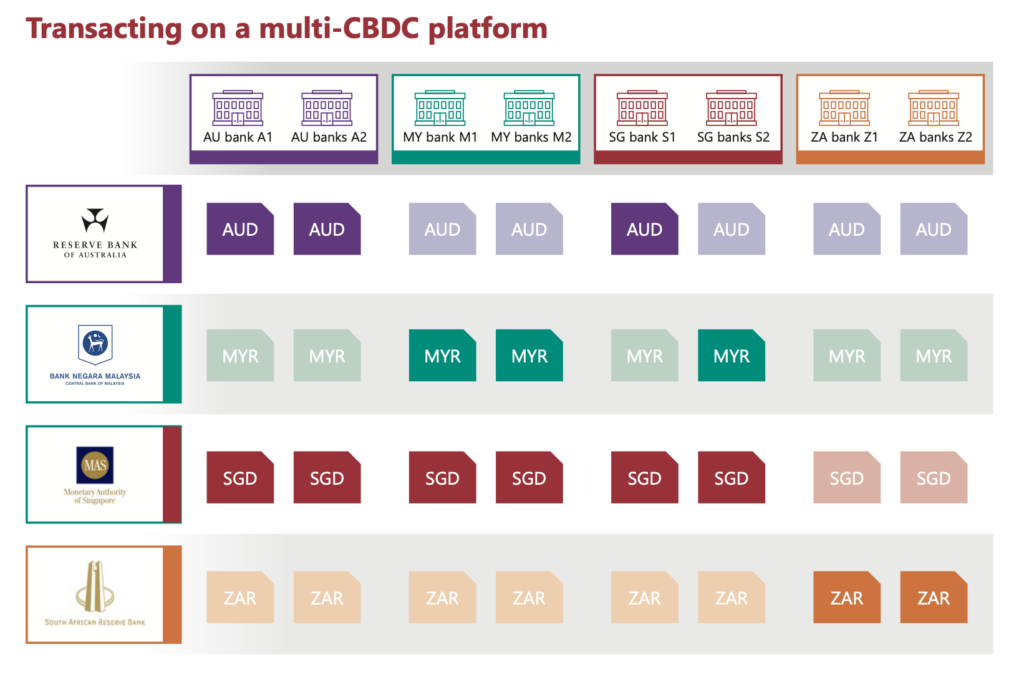

The BIS report uses the following example illustrated in the image below. If a commercial bank based in Singapore (S2 in the illustration) has a licence to operate in Singapore and Malaysia, it would have access to the national payments systems and the currencies of both these countries, namely Singaporean dollars and Malaysian ringgit.

If the bank is given access to the same multi-CBDC platform as the rest of the members, it means that S2 has access to all CBDCs hosted on the network, even the currencies of countries with which it doesn’t have a licence. All participating banks can hold all CBDCs, meaning they can transact directly with each other on the platform. As such, Bank S2 can hold the CBDC version of Australian dollars or South African rands and use it for direct payment to an Australian-based bank or a South African bank.

How do banks and governments transact with each other at the moment?

With difficulty. Even a single cross-border payment must go through various intermediaries and banks to be cleared on the other end. It’s a costly and time-consuming process that involves regulatory hurdle clearing related to anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism measures. The bottom line is that it’s complicated and expensive to send money overseas, even for governments.

Who decides which central banks get access to a certain platform?

The ultimate decision would lie with a governing body that oversees each platform.

Is a CBDC just a bigger, fancier Bitcoin?

No, the two are fundamentally different in their design. Bitcoin is designed as a peer-to-peer, trustless network that requires no intermediary. At the centre of Bitcoin lies decentralisation, whereby the network is managed by thousands of nodes spread across the globe. New Bitcoins are created by miners through the proof of work protocol.

A CBDC aspires to many of these goals, especially in reducing the time and money it takes to make cross-border payments, but the tokens, or coins, are issued by a central bank, the same way that hard cash is printed by the same institution. On the platforms where nodes are required, these nodes will be controlled by a centralised party, in this case, the government.

Where does this leave cryptocurrencies in South Africa?

It’s a good question that both sides of the industry are still trying to come to terms with. Experts say that while CBDCs are inevitable, it’s still a long way from being a relevant global player in the payments system, and that cryptocurrencies and digital assets will continue to fill a niche. Regulation permitting, retailers and governments may, for example, use Bitcoin to bolster their treasuries, while using CBDC as a payment rail. There are many ways in which this can play out, but it also means many opportunities. The takeaway is that cryptocurrencies in their various forms are evolving and are here to stay.

Discover

Discover Help Centre

Help Centre Status

Status Company

Company Careers

Careers Press

Press