Printing cash fast: How the Bank of England pays for things

What is the Bank of England?

The Bank of England (BoE), founded in 1694, is the UK’s central bank and sets monetary policy for the UK economy. This includes setting interest and inflation rates, printing money, performing quantitative easing and helping run the economy.

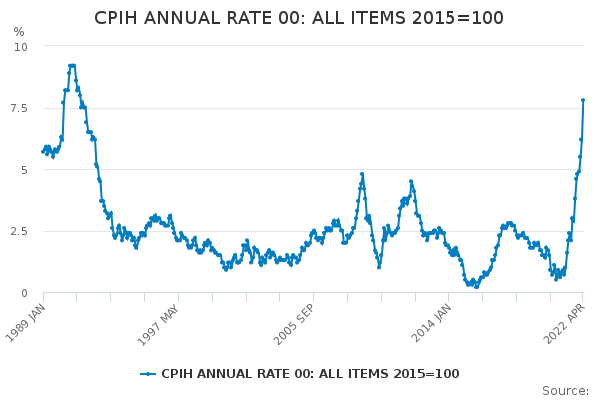

Inflation is measured using the consumer price index (CPI) which aggregates changes in the cost of goods, such as food, energy, alcoholic beverages, housing and clothing, etc.

As seen in the chart below, inflation has risen above 7% for the first time since the early 1990s.

The UK government sets the BoE a target to keep inflation at a rate of 2%. However, inflation has risen by over 7% since 2020. This means the Bank’s Governor, Andrew Bailey, must write a letter to the Challenor of the Exchequer outlining the causes and what the bank plans to do. The primary mechanism the bank then has to reduce inflation is raising interest rates. The idea is this makes loans more expensive, consequently reducing the amount of cash in circulation to bring down the cost of goods.

What can be done about rising inflation?

Inflation measures how the spending power of currencies decreases over time. As this happens, purchasing power decreases, so you need more money to buy goods than you did before. Over the last two years, the BoE has printed money to pay for government spending on covid relief programmes, such as the furlough scheme. According to research by the New Economics Foundation, 99.5% of covid spending — totalling around £412 billion — was paid for with printed money.

The consequence of this is that there is now an additional £412 billion circulating in the UK economy that wasn’t there before. The UK is not alone in this, however. The Federal Reserve, the US’s central bank and counterpart to the BoE, also printed money to pay for covid relief. In 2020, the Fed printed so much cash that this now accounts for 20% of all US dollars ever printed.

The rising cost of energy has also prompted a rise in inflation across the global economy, leading to a knock-on effect on the cost of other goods and services.

How does money printing work?

Money printing, or quantitative easing, is the process the BoE uses to pay for government spending. Although it’s called “printing” this isn’t strictly accurate. When the government borrows money to pay for spending, the bank essentially meets the cost of the loan and creates an IOU (I owe you) from the government in what’s called a bond. By meeting this cost, the idea is this keeps interest rates and the cost of borrowing low. However, the consequence of this is that it creates “new money” in the economy which devalues the purchasing power over the long term. The government then repays the debt to the bond-bearer, in this case, the BoE, in return for interest on the total sum of the loan.

This method can only be used effectively by banks when interest rates are low. Since 2008, central banks have kept interest rates near-zero to decrease the cost of loans. In the short term, this provides a boost to the economy by providing cheap loans, however, over time, this has an adverse effect on inflation and the money supply.

Are there any advantages to rising inflation?

Yes, but it depends on your situation. For governments, companies and individuals with large debts to pay, rising inflation means the cost of the loan is effectively reduced. If you borrow £1 million and then inflation rises, the amount of money stays the same while the purchasing power decreases. This means that £1 million could be much easier to raise to pay off the debt than it was before.

Rising inflation can also lead to higher wages across the economy as employers are forced to offer higher salaries to attract workers. The Bank of England’s Governor, Andrew Bailey, has urged employers to not offer higher wages as a way to curb rising inflation, a comment that received backlash due to rising living costs and the governor’s own salary of over £500,000.

What about deflationary assets like Bitcoin?

Bitcoin was created in 2009 as a deflationary asset in a response to the 2008 banking crisis. There will only ever be a maximum of 21 million Bitcoin created, removing the possibility of “printing” more to pay for spending. Critics argue that Bitcoin could be one of a long line of crypto assets; if Bitcoin’s bubble were to burst, the argument goes, what’s to stop another asset from supplanting it? Fiat currency, such as the pound sterling, is secured by central banks and governments that have a vested interest in keeping the currency safe and secure. El Salvador made headlines last year for adopting Bitcoin as legal tender, which supporters argue is a way forward for developing countries that experience high levels of inflation that makes their fiat currencies practically unusable.

Central banks have argued that although they see the benefits of cryptocurrencies, they believe that CBDCs (central bank digital currencies) could be a preferred way forward. Critics argue that this would return the financial system to the problems presented by fiat currencies, such as excessive inflation and money printing practices that can erode consumers’ savings.

To learn more about inflation, check out our learning resources.

Discover

Discover Help Centre

Help Centre Status

Status Company

Company Careers

Careers Press

Press